Below is Ben Orkin’s story on his vision, journey, and experiences rafting The Kunene River. Read about his incredible descent full of adventures in every way; from Namibian militia, flips in big water, heli-evac attempts, to crocodile attacks.

The Kunene River

The Kunene River, stretching from the Highlands of Angola to the border of Namibia offers some of the most unique scenery on its journey to the Atlantic.

The rivers weave its way through the desert in a series of mountains, gorges, valleys, and finally massive sand dunes as it nears the coast. In the gorges downstream of Epupa Falls, the most formidable whitewater is encountered with numerous Class V rapids and portages required. In the valleys, nomadic Himba tribes are encountered, and the sand dunes are home to desert lions, leopards, and ostriches. The Kunene River is known for its aggressive crocodiles that are found throughout the river. To our knowledge, the river had been previously attempted four times the most recent being in 1993.

We were drawn to the Kunene due its remoteness, wildlife, culture, and challenging whitewater. Our team of four consisted of my dad Arthur, who has been rowing for nearly 45 years, me and my brother who grew up whitewater rafting and kayaking, and a good friend and volcano expert Chris Horsely. Together, we had completed other expeditions in Madagascar and Mexico while we waited for our chance on the Kunene.

The challenges faced, portages and rapids.

Any attempt on the Kunene is wrought with challenges.

Before our team of four even got to the river we were faced with wildly fluctuating water levels (drought to floods in a matter of weeks), acquiring the appropriate permits, handling logistics and gathering the necessary equipment for a three week long unsupported mission. After flying with 15 checked bags and 6 carryon’s, including 3 Hyside Thundercats from Colorado to Namibia, overzealous customs officials almost denied us entry.

After floating for four days above Epupa Falls, we were denied entrance to the river below the falls and threatened with arrest by the Namibian military, and then after Epupa Falls, were faced with extremely tough whitewater, must make eddies, and complex portages, not mention the crocodiles.

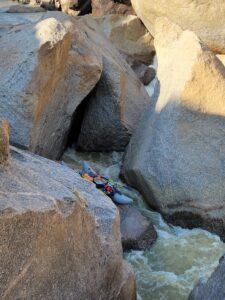

The first gorge below Epupa proved quite intimidating with 3 back-to-back unrunnable rapids (at our high-water levels) which forced 2 long portages and lining. We snapped a rope while lining a cat and nearly lost it as it floated downstream unmanned. Further downstream, we all almost missed a must make eddy above a large rapid.

In a freak accident, Arthur sustained a severe injury to his ribs that likely required evacuation. Unfortunately, we were on the Angolan side of the river (without visas or necessary permission) and in an extremely deep gorge with limited sat phone communications. After failing to arrange an evacuation, we were forced to continue downstream and tend to Arthur’s injuries as best as we could.

Just below, we faced our worst crocodile attack. Arthur was able to recover to a point where we all felt it was reasonable for him to continue. After celebrating his 65th birthday above a massive gorge, we spent the next 10 days in and out of narrow gorges running incredible whitewater and portaging what we found too intimidating.

Thankfully, we were mostly able to portage with the Thundercats inflated and frames/oars still attached.

Days on the Kunene

Our days on the Kunene were often incredible and intimidating. We had higher water than any of the previous trips and the difficulty of the rapids seemed to reflect that. The beauty of the river is indescribable. Unfortunately, a dam threatens the stretch below Epupa Falls. I would one day like to go back to the Kunene before its dammed. We functioned almost flawlessly as a team to have a highly successful trip down the Kunene. We often woke up early in the morning to take advantage of cooler temperatures and lower croc activity.

I had spent countless hours analyzing satellite imagery and developing a map of the river to help identify rapids we needed to scout (and where to scout from) and what we would likely need to portage. We would scout as a team and decide on the best running order for both safety and photography. We had purposefully brought three catarafts for four people, as we felt having a backup rower in case of injury would be useful (and it was) the passenger was also able to take photos and videos and be extremely helpful on croc look out. We stayed close together through the flats to help identify and avoid crocs.

We had amazing encounters with nomadic Himba tribes – including helping them shuttle their goats across the river – and sometimes offered money in exchange portaging. We hiked up slot canyons and spent afternoons exploring the sand dunes near the ocean. We saw ostriches, oryx, and springbok. We fished somewhat successfully.

Towards the ocean, the weight of the expedition began to take its toll. Being towards the bottom of the food chain and faced with huge rapids is an interesting perspective.

We would try to paddle in the cooler mornings that were quite foggy to avoid the crocs, and despite the temperature, we would often take off all our splash gear before the rapids and but it back on after the rapid. Our thought process was that anything that limited swimming speed and ability, such as splash gear, would be a huge liability with the number of crocs in the water. Having ended up in the water twice myself, I can certainly attest to just how fast I wanted to be out of the water.

Rapids with Crocodile Consequences

We almost missed the eddy for this rapid as there is a quite continuous section of read and run Class 3 and 4 above it, and its somewhat on corner. At the last minute, we were able to eddy out on river right and scout. This is where Arthur suffered his rib injury and we spent the better part of the day trying to unsuccessfully arrange for a heli-evac. Realizing we had to get Arthur downstream, the team decided that Sam would run one Thundercat through the rapid alone.

Being the first boat down meant Sam would have no boats downstream to help in the event of a flip, swim, or croc attack. Chris stationed himself with a throw rope immediately below the drop and I traversed the cliff a couple hundred yards downstream where the river narrowed before careening around the corner to the next drop. We figured Chris would likely be able to recover a swimmer and/or boat, and I would be positioned far enough downstream to clean up any remaining mess.

Unfortunately, Sam did not re scout the rapid and the water level in the narrow gorge had changed quite drastically since that morning, shifting the entrance a few yards to the right. Sam hit is intended entrance which was now the wrong entrance at this flow. Despite his valiant attempts at high siding on the right tube in the hole and then on the left tube against the cliff, he flipped.

He popped up just downstream next to the cat in a bobbing eddy. He was able to re-flip the Thundercat by himself and ferry back to river right to help set safety for me and provide me with invaluable beta. Armed with his beta, I was able to successfully run my cat and Arthur’s cat through without issue. With all three rafts downstream of the rapid, we were tasked with getting Arthur around the rapid and into the cat and then downstream to camp. Chris volunteered to row and the whole team got to watch me and my cat get attacked by a rather sizeable croc.

Final Thoughts on Gear Choices, Challenges, and Choosing a River Trip Unlike Any Other

Exploratory raft descents in Africa have typically been with paddle assisted oar frames and kayakers. I had planned a version of the trip with that framework in both 2021 and 2022 but cancelled due to COVID and then drought. In 2022 we diverted to run a river in Madagascar. While leading that trip, my thoughts often wondered to what the Kunene would be like. I knew the Kunene would have bigger rapids, harder/longer portages, and way more aggressive crocs.

In my mind, it become increasingly obvious that the risk the Kunene crocodiles posed outweighed my kayaking-with-crocodiles risk tolerance by quite a large factor and I was unable to find other willing kayakers. And, if there were no kayakers, big oar boats with paddle assist passengers wouldn’t really be safe either. What if one raft with three people eddied flipped and 3 people washed down to an eddy full of crocs?

Thoughts of trying to portage 14 or 16 foot rafts through the gorges also made the trip seem intimidating. Even the logistics of bringing rafts seemed too complex. We had imported one raft into Madagascar, and it had been an absolute nightmare (and the raft was rather low quality). We would have to import the same brand of raft into Namibia to run even harder whitewater. But then it clicked. If I made the painful decision to cut out half the team members, cut out the kayakers, and replace the rafts with catarafts, our attempt on the Kunene would fall within my risk tolerance level. The Thundercats were light enough to fly with so we could avoid importing/exporting issues, each Thundercat would be easier to portage than a raft, there would be no kayakers (a.k.a. croc bait), and if a cat flipped, only one or two people would end up in the water. We could flip the cats back over midstream. To me, it was an untested theory and it took until about day 10 to realize just how well my theory was working.

The Thundercat 14.0 were nimble enough to boat scout a bit like a kayaker would and offered superior performance as compared to a raft. We ran much harder whitewater with the Thundercats than we would have otherwise, which limited the portages. Portages, while never easy, were certainly made exponentially better with the cats. We were also able to drag, line, drop, push, and shove the boats through shallow sections on the sides of rapids.

My biggest concern with the cats was the risk of a croc attack – especially for the person sitting at the back and at the rower’s feet. We designed and fabricated cat floors to help eliminate the risk of an attack on the rower and similar “croc catcher” net behind the one passenger seat to help eliminate the risk of a croc attacking from behind. We were subjected to several croc charges and a few attacks throughout the three weeks. To help eliminate the threat, we would often row with the tubes of the cats overlapping (to appear bigger). When a bold enough croc did attack, they often times would go for the tubes.

Although just searing images burned into my memory, I have vivid recollections of the crocs trying to wrap their jaws around the cat tubes. For whatever reason, they were unsuccessful. After the Kunene, I am a huge believe in the Thundercat’s performance and durability, and will definitely bring them back for a second trip.

Ben Orkin is an outdoor enthusiast with a love for adventure. Read more on his speed record: Grand Canyon Speed Record

Ben Orkin

Courtesy of Pamela Wolfson Via AP